Over the last 20 years or so, airlines have experimented with many ways to lure consumers away from online travel agencies (OTAs) and toward their own websites. The most effective strategy so far: prevent OTAs (and apps such as Hopper) from displaying their prices. Southwest has long prevented third-party sites and apps from selling its fares, which is why you’ll never see Southwest on Google Flights or Priceline. Delta Air Lines over the last few years has withdrawn permission to display its fares on about 30 sites and apps, such as Hipmunk, Fare Compare, and Hopper.

And now jetBlue has removed permission for a dozen mostly small OTAs (most notably Vayama) to sell its fares.

Other tactics in this assault on OTAs include offering more frequent flier miles or points if booked directly with the airline, promo codes which can only be redeemed on the airlines’ websites, and ticket discounts (for example, British Airways offers lower fares to AARP members, but only if booked at BA.com).

An industry insider told me that Delta may one day add larger OTAs to its “banned list” and jetBlue in its announcement restricting access to those 12 sites hinted that it might not be finished limiting access to its inventory.

There are several reasons why airlines are divorcing from third-party sites, but there are still some good reasons why consumers should consider OTAs anyway.

I recently searched for a flight from New York to Detroit on Expedia.com and compared the same flights and dates on Jetblue.com, leaving January 23 returning January 30. The experiences could hardly be more different. jetBlue shows three airfare classes: “Blue,” “Blue Plus” which includes a free checked bag, and “Blue Flex” which includes two free checked bags and free changes or cancellations. The lowest “Blue” fare for those dates, on connecting flights, is $191.62 round-trip per person on JetBlue.com.

Then I looked at Expedia to book my imaginary New York to Detroit trip. It only showed the lowest “Blue” fare on jetBlue, which means the airline misses a chance to lure consumers into other fare options. JetBlue also forfeits any opportunity to market its credit cards, vacations, and other products if a consumer doesn’t book directly on Jetblue.com. Plus, the airline probably has to pay Expedia for a referral (although exactly what OTAs charge airlines and hotels for sending them business is a closely guarded secret).

Free airfare if I book a hotel?

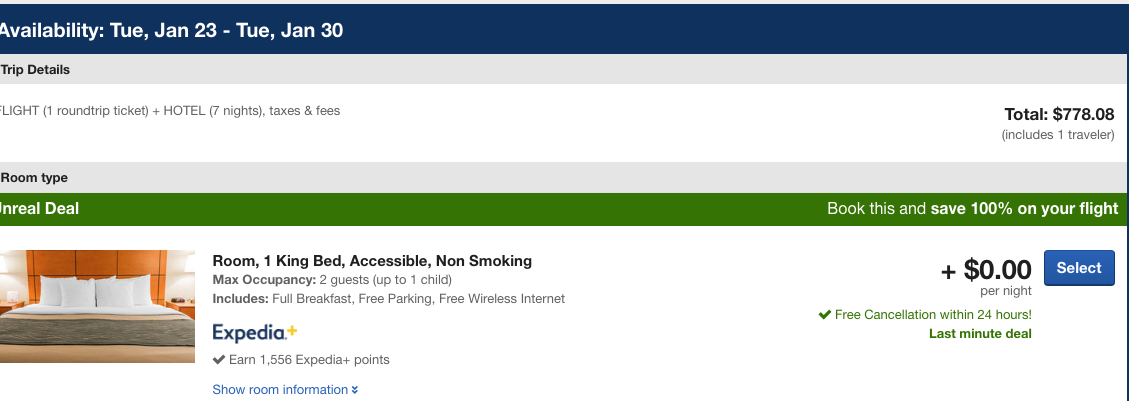

In any case, Expedia had other plans for me. It didn’t suggest that I fly on jetBlue at all. Rather, it offered a nonstop basic economy airfare (meaning I’d have to pay for a carryon bag unless I have status in American’s frequent flier program or carry one of their co-branded credit cards) on the outbound flight with a return on Delta, and further suggested that if I book a one-week hotel stay at the Comfort Inn Metro Airport along with my airfare, then the airfare would actually be free. Really now?

Yes, really. Or almost free. On Comfort’s website, that one week stay was offered at a lowest rate of $770. But Expedia would sell me a round-trip airfare plus the same room type, same dates, same hotel for $778. So yes, booking air and hotel together basically meant that the airfare would cost me $8 (or, as Expedia put it, I got a 100% discount on the flight).

So that is one clear advantage that OTAs offer and why they haven’t gone out of business despite years of attacks by their airline partners. Not only did Expedia save me money by suggesting I combine airlines (in this case, American plus Delta, a strategy that Jetblue.com would of course not propose) but it offered the flights basically for free. The hotel buying power of Expedia and its ilk offer advantages that most airline sites cannot match, plus they allow passengers to combine airlines in one booking to get a lower airfare. And those are perhaps good reasons, along with avoiding referral fees, why airlines would rather that you book direct with their websites.